|

Small

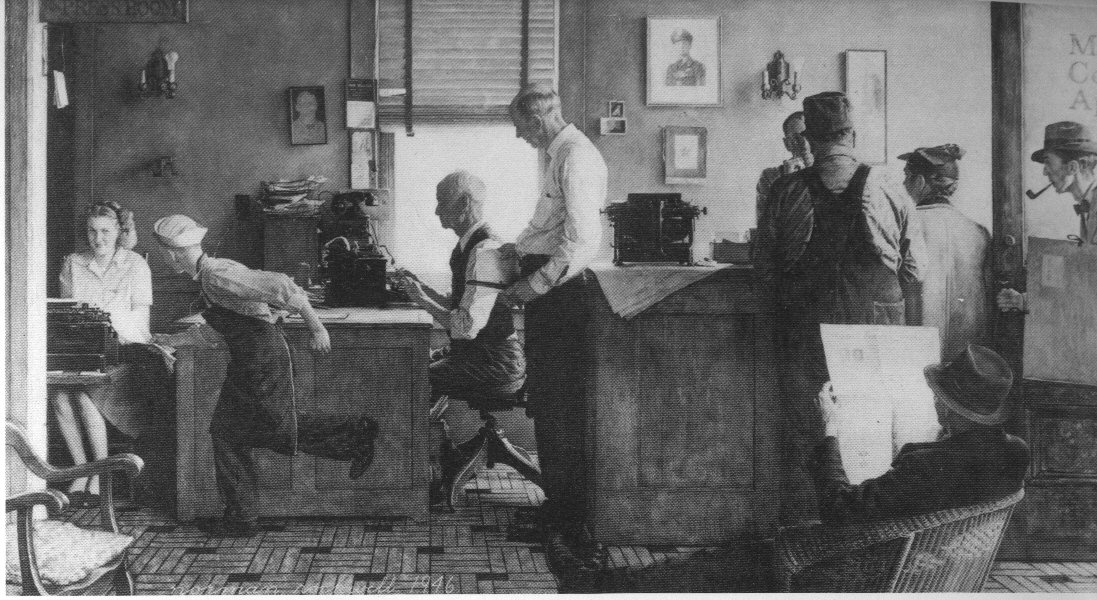

Newspaper Lifted In Painting Still Going Strong

Not Much Has Changed Since Rockwell's Visit

St.

Louis Post-Dispatch

December 29, 1996

By Jim Salter of The Associated Press

The

manual typewriters are gone, replaced by Power Macintoshes.

A printer's devil no longer sprints around the office as

press time nears - these days, the newspaper is printed in

another town.

But otherwise, things haven't really changed much in the 50

years since Norman Rockwell immortalized the weekly Monroe

County Appeal with his painting of "The Country

Editor."

The

newspaper is still all local, the news mostly good. There

are features and lots of sports, but still plenty of items

on who's visiting from out of town, what's happening at the

Baptist church and who's in the hospital.

Now, as in 1946, the Appeal, like about 300 other weeklies

in Missouri, is read and read again, a fixture in the living

room until the next one arrives.

"I go over it pretty well, then I read it again and

find things I missed," said Zelma Menefee, 85, a stack

of newspapers the only sign of mess in the living room of

her white frame home in this northeast Missouri town.

"Then when I'm done, I cut it up to go in my

scrapbooks."

A lot of people do. For small towns such as Paris,

population 1,500, the newspaper is the only source of local

news.

"We need it," said Floyd "Doc" Barnett,

86, who still sees patients seven days a week. "It

means life. It tells us what's going on in our little

town."

Rockwell came to Paris in 1945 to capture the essence of the

small-town newspaper office for the Saturday Evening Post.

He spent a couple of days here, sketching, attending a

country ham supper in his honor at a local ta vern, speaking

to the Rotarians. Rockwell then returned home to Vermont to

paint, and his two-page color likeness appeared on May 25,

1946.

The focal point of the painting is longtime Appeal editor

Jack Blanton, who was by then already something of a legend

for his well-crafted editorials, deep religious beliefs and

occasional bouts of eccentricity.

Once, during a drought, Blanton ran a banner front-page

headline that read, "LORD, WE CONFESS OUR SINS, WE ASK

FOR FORGIVENESS, WE PRAY FOR RAIN." A rainstorm soaked

Paris the day the paper hit the streets.

Rockwell's painting portrayed the busy Appeal office minutes

before the paper went to press. The Saturday Evening Post

described it this way:

"Blanton is shown batting out a last-minute editorial.

That picture above his desk is one of his father, who

founded the Appeal. The gold-star service flag hangs beneath

a picture of a grandson of Blanton's, who would have

succeeded him as editor if he hadn't lost his life in the

Army Air Force. Peering over Blanton's shoulder is the

Appeal's printer, Paul Nipps, whose experienced eye is

gauging the number of printed lines the editorial will take

up."

The painting also shows customers buying a subscription and

other office workers scurrying about. And walking in the

door, trademark pipe jutting out, is Rockwell himself.

The Appeal workers, all of whom have since died, had their

moment of celebrity. Several big-city dailies reprinted the

painting, leading Blanton to write, "Waking up to find

themselves famous, the Appeal office force now knows how the

man felt who fell in the river and came up with his pockets

full of fish."

The painting still hangs prominently in the Appeal lobby,

another copy in the office of owner Dick Fredrick.

The old building was torn down years ago, making way for a

parking lot. Computers and laser printers have replaced

typewriters and linotype. Printing is too expensive for most

weeklies - the Appeal is now printed by the daily in nearby

Mexico, Mo., the Ledger.

But much remains the same.

A handful of staffers still work long hours in an often

hectic office. Managing editor Julie Warren and

advertising/circulation manager Amber Bounds are the only

full-time workers. Pat Reading is able to write all the news

working part time. Another part-timer sells ads, and a high

school senior comes in afternoons to serve as proofreader.

And everyone pitches in to paste pages, answer phones, stuff

inserts, bundle papers, even deliver them to stores.

"We never stop - we run continuously," Warren

said.

The 1,600 Appeal subscribers appreciate the effort. Another

400 or so papers are sold each week over the counter, with

customers lined up on Wednesday afternoons, waiting for the

paper to arrive.

"I've had older ladies call me in tears because their

paper didn't come in the mail," Bounds said.

Like their daily brethren, small-town weeklies have declined

in numbers through the century. About 800 existed in

Missouri in 1900; that's down to 300 now. And one-fourth of

those are suburban or alternative papers from the state's

metro areas and bigger towns.

Barnett has been taking the Appeal since he moved to Paris

59 years ago. Menefee has been a subscriber 60 years.

"We're still just a hometown paper," Reading said.

Readers say that's the appeal of the Appeal.

"Wouldn't know what to do without it," Menefee

said. |